Are the Workers OK? Are the kids OK?

Last week, Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews described Victoria's workers' compensation system as "fundamentally broken," with the unsustainable cost of claims of "stress" and "burnout" bringing on a crisis.

Minister for WorkSafe, Danny Pearson, highlighted that when WorkCover was introduced in 1986, mental health claims comprised 2 per cent of claims. He said that figure was now 16 per cent, and those claims accounted for 50 per cent of WorkCover's cost.

I am involved in workforce leadership, culture and safety in a state-owned utility. We were briefed on the unsustainable increase in stress and burnout claims in the Victorian public sector. As a result, we took steps to minimise the risk to our workers and the organisation. As a former workers' compensation lawyer in the 1980s, I had predicted that the rise in public sector claims would risk bringing down the system as it had done last century.

This brings up important questions.

What could be driving the marked rise in stress and burnout claims?

What factors might lead so many Victorians to experience burnout or stress to the point of being unable to work?

Is this problem unique to workers in Victoria or Australia?

Notably, we know that more than one in five Australians is on a prescribed anti-depressant and/or anti-anxiety drug. Who knows how many more are self-medicating?

A Global Epidemic of Stress and Burnout?

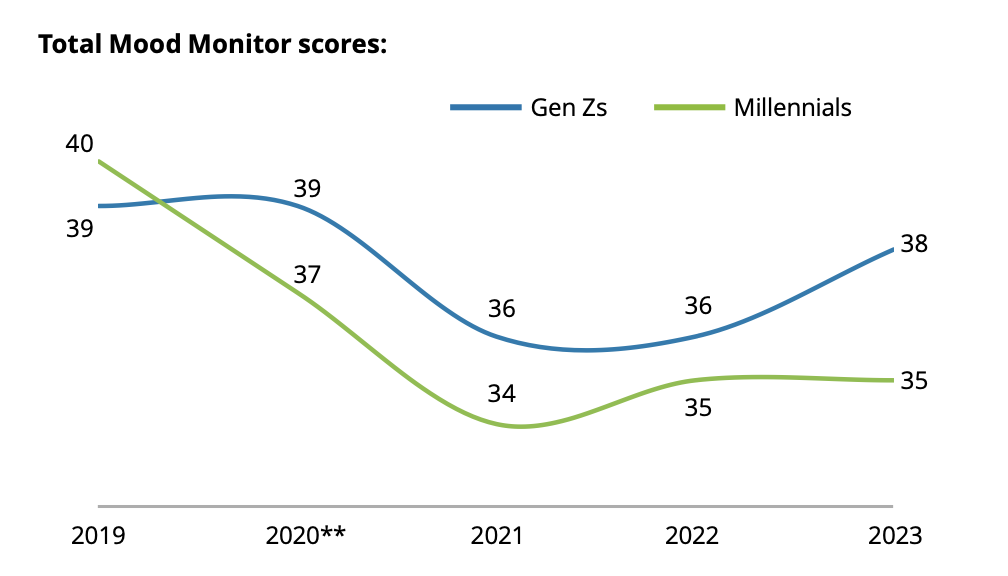

Last week too, Deloitte published its 2023 Gen Z and Millennial Survey surveying 22,000 Gen Z and millennial respondents across 44 countries to explore their attitudes towards work and the world. The survey revealed low levels of optimism among these generations regarding economic and sociopolitical situations.

The survey highlighted that stress and anxiety levels remain high, with burnout on the rise. Work pressures were identified as a major driver of burnout among Gen Zs and millennials. Approximately 52% of Gen Zs and 49% of millennials reported feeling burned out.

Using the World Health Organization's criteria for burnout, the survey asked respondents about specific feelings experienced while working. The results showed that 36% of Gen Zs feel exhausted all or most of the time, 35% feel mentally distanced from their work, and 42% often struggle to perform to the best of their ability. Similarly, the numbers were nearly as high among millennials. Approximately 46% of Gen Zs and 39% of millennials reported feeling stressed or anxious at work all or most of the time.

Deloitte believes various factors contribute to the stress and burnout experienced by Gen Zs and millennials. Concerns about their longer-term financial futures, day-to-day finances, and the health/welfare of their families were identified as top stress drivers. Additionally, mental health concerns and workplace factors such as heavy workloads, poor work-life balance, and unhealthy team cultures were also significant contributors.

The chart below is the Deloitte Gen Z and Millennial Survey Mood Index on Gen Zs’ and millennials’ optimism that the world and their places in it will improve.

Are the Kids OK?

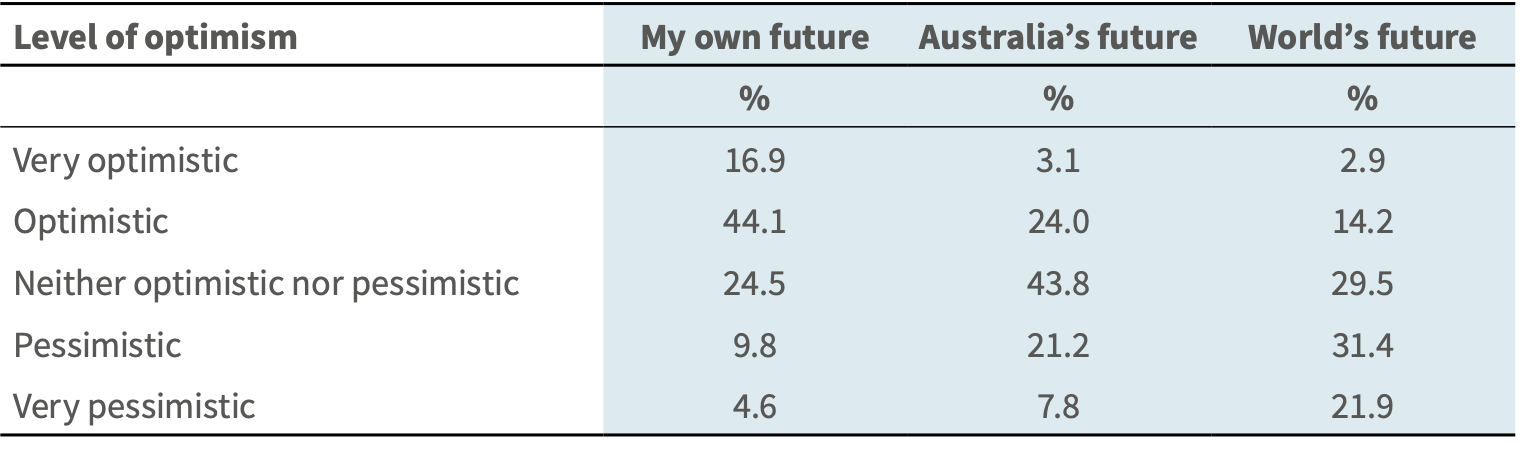

"Are The Kids OK?" is the provocative question posed by Dr Quentin Maire, Nadishka Weerasuriya, and Associate Professor Jenny Chesters in their University of Melbourne Life Patterns research project 2022, which surveyed Year 11, Australian students. The results revealed a palpable sense of pessimism amongst the respondents: fewer than half felt optimistic about Australia's future, and a mere one in six expressed confidence in the world's future. In fact, over half of the students (53%) were pessimistic about the world's future, echoing a prevailing sense of hopelessness when contemplating the fate of their generation worldwide. Similarly, 14.4% of participants expressed pessimism about their personal future, with 29% feeling the same about Australia’s future.

I was fortunate to attend an audience with the Dalai Lama, where he emphasised, "Helping children to stay hopeful and still optimistic despite the difficulties is very important."

Professor Lea Waters, Gerry Higgins Chair in Positive Psychology at the University of Melbourne, also asserted, "Optimism is the most important psychological ingredient we can cultivate in our children. It is the secret weapon of strength-based parenting."

I can't forget the words of Michele Borba, Educational Psychologist: "Optimistic kids view challenges and obstacles as temporary and able to be overcome, so they are more likely to succeed. Teaching children optimism begins with us. Kids adopt our words as their inner voices, so over the next few days, tune in to your typical messages and assess the outlook you offer your kids."

We established the Centre for Optimism in response to this rising tide of pessimism. We're driven by a mission to nurture hope and positivity. Drawing from a lifetime of optimism, four years of intensive research into Australian leadership, and five years of research on optimism focused on the questions, "What makes you optimistic?" and "What makes you feel optimistic?" we aim to lift the pervasive 'fog of pessimism.'

We encourage everyone to add a little optimism to their everyday interactions. This could be as simple as modifying a greeting to include, "What's been the best thing in your day?"

At the Centre, we recommend exercises such as "My Optimism Superpower" and "Imagine My Best Self". We also host popular workshops at conferences, workplaces, and schools. Through these endeavours, we empower individuals to envision and build a positive future for themselves, Australia, and the world.

However, this problem is not unique to Australia. Last year, Singapore's Senior Minister & Coordinating Minister for Social Policies, Tharman Shanmugaratnam, declared, "We have entered an era without precedent, certainly not in living memory, and it has led to a loss of optimism almost across the world."

His call to action was stirring and precise, "Creating bases for optimism has to be our central task everywhere in the world and through global collaboration. We must create bases for optimism to see ourselves through this long storm and to emerge intact; emerge a better place, and it can be done."

At the British coronation of King Charles III, Penny Mordaunt MP, UK's Leader of the House of Commons and Lord President of the Council, made her mark with the sword she carried.

Penny is more important for her wise words last year: "The faultline in politics at the moment is not between left and right but between optimists and pessimists. We need optimists for the next tough shift."

Her words resonate beyond the political landscape. They speak to us all, underlining the vital need for optimism in all sectors of life.

In the face of this global loss of optimism, we must rise to the challenge. It's not just the politicians, the leaders, or the educators; each of us has a role to play in this. We must strive to be a beacon of optimism, a ray of hope piercing the fog of pessimism.

So, as we confront the trials and tribulations of our times, let us reframe our mindsets and conversations. Let's ask, "What's been the best thing in your day?" Let's exercise our "Optimism Superpower" and imagine our best selves.

Let's foster hope and positivity in our children, workplaces, communities, and world; through this collective effort, we can emerge from this storm intact, better, stronger, and more optimistic about the future. This is our call to action. This is our challenge. And this is a challenge we can and must rise to.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.svg)